The evolution of Infrastructure as code

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is the automation approach to defining, provisioning, configuring, and managing infrastructures. If you are developing services at scale today, chances are you already very well know what IaC is. It’s become a core practice in today’s cloud age where microservices are prominent, release cycles are shorter and teams deliver small changes rapidly.

In the past 5 years, I’ve had a fair interaction with IaC, the first on a team where we used Chef to configure a fleet of VMs in the data center. Eventually, as services moved to the cloud, our team used Terraform. My next team used Cloudformation for our services on AWS and my current team uses Ansible for our Azure infrastructure.

One thing I learned here is how these tools vary in terms of their capability of configuration management vs provisioning, creating mutable vs immutable infrastructures, language styles- imperative vs declarative, community support, and overall maturity. Moreover, I realized that even though the tools for IaC change, the fundamental paradigms that contribute to having a successful infrastructure as code remain the same. Recently, I read the book Infrastructure as Code by Kief Morris and several concepts from the book focused on how teams can optimize their IaC for change and were interesting enough that compelled me to share some notes here.

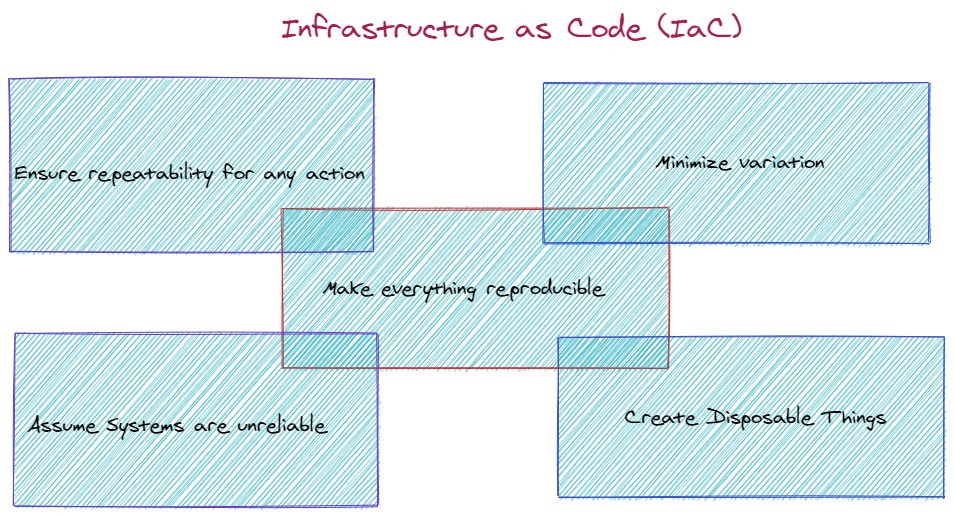

The book sets the premise by distinguishing between the Iron age (static pre-cloud systems) vs Cloud age (dynamic cloud-native systems) of infrastructure. Kief illustrates the 5 key principles to understand when working with IaC for your infrastructure:

Principle 1: Assume Systems are unreliable

Modern cloud-scale infrastructures involve hundreds and thousands of resources. The system design should ensure uninterrupted service when underlying resources change.

Principle 2: Make everything reproducible

The recoverability of a system depends on the ability to rebuild its parts effortlessly and reliably. The effortless part here refers to eliminating the need to make any decisions about how to build things by defining configuration settings, dependencies, and software versions as code.

In addition to allowing failed systems to recover, reproducibility also ensures consistency, availability, and scalability. It creates psychological safety against risk and fear of making changes, allowing teams to handle failure with confidence. One pitfall is that often, teams can find themselves dealing with a snowflake which is an instance of a system or part of a system that is difficult to rebuild. A snowflake system is one when the team is not confident to safely change/ upgrade it or fix it when broken. Such a system can be replaced by writing code that can replicate the system, running the new system in parallel until it’s ready.

Principle 3: Create Disposable Things

One of the main ideas of cloud-native software is making the pieces of your system malleable. A system that is itself dynamic allows teams to gracefully add, remove, start, stop, change, and move its parts. This creates operational flexibility, availability, and scalability.

Principle 4: Minimize variation

As a system grows, it gets challenging to understand, change, and fix it. Low variations result in more manageability as it’s easier to manage one hundred identical servers than five completely different servers. For example, variations can be in terms of having multiple OS, application runtimes, databases, or having multiple versions of these.

Identical systems can suffer from Configuration drift which is a variation that happens over time across systems that were once identical. A key culprit in causing a configuration drift is making manual changes. It can also happen if automation tools are used to make ad hoc changes to only some of the instances. Configuration drift makes it harder to maintain consistent automation.

Principle 5: Ensure that you can repeat any process

The principle of repeatability builds on the reproducibility principle. Teams should be able to repeat anything they do in the infrastructure. Embracing automation is key to repeatability. One of the core features of effective infrastructure teams is their strong scripting culture. Ideally, if you can script a task, script it.

Infrastructure Platforms

The technology stack, tools, or platforms vary from team to team or company to company. Therefore, having a model for thinking about the high-level concerns of a platform, its capabilities, and the infrastructure resources required to provide these capabilities is crucial.

Modern infrastructure systems are complex and comprise applications (application packages, container instances, serverless code), application runtimes(servers, container clusters, database clusters) and infrastructure platforms (compute resources, network structures, storage). These infrastructure platforms can be public IaaS cloud services, private IaaS cloud products, and/or bare-metal cloud tools. The infrastructure platforms provide three essential resources:

- Compute resources- virtual machines (VMs), physical servers, server clusters, containers, application hosting clusters, function as a service (FaaS), etc.

- Storage Resources- block storage, object storage, networked filesystems, structured data storage, secrets management, etc.

- Networked resources- network address blocks, names such as DNS entries, routes, gateways, load balancing rules, proxies, API gateways, VPNs, Direct connection, network access rules (firewall rules), asynchronous messaging, cache (CDN), service mesh, etc.

At this point, we can agree on how diverse and vast the infrastructure domain is today. Teams have to work with these resources and services to arrange them into useful systems to build the ‘infrastructure’ part of IaC. IaC in the cloud age is based on three principles:

- defining everything as code

- continuously testing and delivering all work in progress

- building small, simple pieces that can be changed independently

Kief has a very good deep dive into the core principles for an infrastructure that can change rapidly and reliably. This article summarizes the 1st principle- Define everything as code. By defining everything as code, teams can leverage speed to improve quality. Some candidates in the system that can be defined as code are- the infrastructure stack, the elements of a server’s configuration (packages, files, services, user accounts), configurations for ops services, server role, server images, validation rules (automated tests and compliance rules), etc. Idempotency is an important characteristic of IaC. Idempotent code means re-running it any number of times will not change the output or outcome.

Version Control and IaC

Similar to any other code, infrastructure code (except unencrypted secrets like passwords & keys for obvious security reasons) should leverage a version control system (VCS) as it provides benefits like:

- tracing the history of changes

- revert to the previous state if a change breaks something

- enabling CI/CD

- single source of truth for the team to be aware of the infra

- the code is the documentation for the infra

I can attest to these benefits as I often find myself referring to our infrastructure code in the repo to check on configuration details, incremental history, who changed what, etc. instead of navigating the cloud portal.

Implementation principles

As with software engineering, infrastructure code needs to maintain the code quality. Keeping the codebase clean, easy to understand, test, maintain, and improve is vital to making updates and evolving the infra systems easily and safely. Two key implementation principles to understand are:

- Mixing both declarative and imperative code is a design smell.

- Infrastructure code should follow code quality practices, such as code reviews, pair programming, and automated testing.

- The team should be aware of technical debt and strive to minimize it.

Infrastructure stack and its patterns

An infrastructure stack is a collection of infrastructure elements managed as a group. There are several patterns to structure the stack. A challenge with infrastructure design is deciding how to size and structure stacks. Let’s look at the comparison here:

| Pattern | Description | Motivation | When to use | Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monolithic Stack | too many elements, tight coupling | single stack easy to maintain | System is small and simple | change is expensive, large blast radius, slow provisioning, hesitancy to make changes |

| Application Group Stack | multiple related applications or services provisioned and managed as a group | easier to manage the application as a single unit | single team owns the infra & deployment of all pieces of the app | inefficient if some parts change more often. The time, risk, and pace of changes are combined. Can grow into monolithic stack |

| Service Stack | manage the infra for each deployable app component in a separate stack | aligns the boundaries of infra to the software that runs on it, service team owns the infra for their software | microservices, autonomous teams | unnecessary duplication of code |

| Micro Stack | infra for single service divided across multiple stacks | change rate varies for parts of infra, different characteristics of parts make it easier to manage separately | parts of infra have different lifecycles | more moving parts add complexity |

Infrastructure Environments

Infrastructure Environments are a group of software and infrastructure resources collectively serving a specific purpose. In today’s fast-paced tech world, it’s a defacto to have multiple environments (testing, staging, production, etc.) also referred to as “path to production”. The most common is TEST-> STAGING-> PROD. There are a few factors that determine the differences in these environments:

- Scale of the environment depends on the purpose of the environment

- Privileges differ for people interacting with different environments

- Testing and delivery strategy differs when the differences listed above exist. The stacks defined in the table above can be used for provisioning these environments.

A common pattern is to have multiple Production environments to provide several benefits- Fault tolerance, Scalability, and Segregation. These systems are identical which means the infrastructure in each environment needs to be consistent. This is a key factor for the adoption of IaC as inconsistencies in environments can create risks of inconsistent behaviors.

Modularity

Modularity is a fundamental software design technique that emphasizes removing redundant implementations and simplifies implementations. Small pieces are easy, safe, and faster to change than larger pieces. How can we apply the same to our infrastructure code?

DORA’s Accelerate research team identified four key metrics for software delivery and operational performance:

- Delivery lead time: The elapsed time it takes to implement, test, and deliver changes to the production system

- Deployment frequency: How often you deploy changes to production systems

- Change fail percentage: What percentage of changes either cause an impaired service or need immediate correction, such as a rollback or emergency fix

- Mean Time to Restore (MTTR): How long it takes to restore service when there is an unplanned outage or impairment. These key metrics are a useful lens for considering the effectiveness of modularizing your infrastructure code.

Characteristics of Well-Designed Components

Designing components in a distributed scalable system can be tricky. It’s the art of deciding which elements of the system to group, and which to separate. Doing this well involves understanding the relationships and dependencies between the elements. Two important design characteristics of a component are coupling and cohesion. Coupling describes how often a change to one component requires a change to another component. Cohesion describes the relationship between the elements within a component. The goal of a good design for the infrastructure code is to create low coupling and high cohesion.

Rules for Designing Components

- Avoid duplication

When designing infrastructure components, following the DRY (Don’t repeat yourself) principle helps reduce duplications. Duplication in code forces the team to make changes in multiple places.

- Rule of composition

To make a composable system, make independent pieces. It should be easy to replace one side of a dependency relationship without disturbing the other.

- Single Responsibility Principle

The SRP says any given component should have responsibility for one thing. The idea is to keep each component focused so that its contents are cohesive.

- Design components around domain concepts, not technical ones

To achieve better reusability, components should be designed around domain concepts. For example, instead of designing a generic server implementation, the design is based on the domain- application server, build server, etc.

- Law of Demeter

This is the principle of least knowledge, a component should not know how other components are implemented. This rule pushes for clear, simple interfaces between components.

- No circular dependencies

In a dependency relationship between components, a provider component creates or defines a resource that a consumer component uses. As we trace relationships from a component that provides resources to consumers, we should never find a loop (or cycle). In other words, a provider component should never consume resources from one of its own direct or indirect consumers.

Final thoughts

IaC is the industry defacto to manage dynamic infrastructures allowing organizations to make changes frequently and reliably. It is a mainstay of good DevOps practice. Practicing successful IaC means applying the same rigor of application code development to infrastructures.